Often in Regency stories the characters will refer to “the latest crim. con.” – usually with titters, blushes, or knowing looks.

For example, in Georgette Heyer’s Cotillion, when Freddy Standish runs into his sister Meg at Almack’s, she exclaims

“Oh, Freddy, I must tell you the latest crim. con. story! You will be in whoops! Only fancy!—it is all over town that Lady Louisa Aldstone and young Garsdale–“

“Lord, I knew that before I went to Melton!” interrupted Freddy scornfully. “And you needn’t tell me Johnny Eppleby fathered the last Thresham brat, because I know that too!”

Huh? Were all these people having affairs also criminals? Chatting during their romantic interludes? It seemed unlikely.

Well, not exactly. I later learned that “criminal conversation” was the legal name for a tort case involving adultery, where a husband sued another man for monetary damages for carrying on with his wife. It was often, but not always, connected to divorce proceedings.

The concept was based on the notion that a wife was chattel – the legal property of her husband. If another man had an affair with her, that was a form of trespass on the husband’s “property,” and the husband was entitled to seek financial compensation for the loss of value in that “property.”

[I can’t help putting quotes around the word ‘property’ as if it were not true, but legally a wife was the property of her husband – for long before, and surprisingly long after, the Regency era]

Divorce was still extremely difficult and expensive in the early 19th century. This would punish the wife, but if an angry husband wanted revenge on his wife’s lover, he would would sue, hoping to win a sizable sum (and perhaps ruin the lover as well)

Basically, a criminal conversation proceeding was a lawsuit by Lord Cuckold against Sir Rake, for fooling around with Lord Cuckold’s wife.

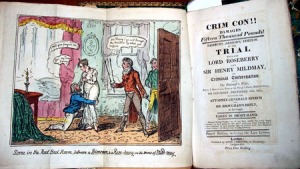

Rosebery v. Mildmay

In this 1814 case, the Earl of Rosebery sued Sir Henry Mildmay of consorting with his wife, Harriet Bouverie. This was not merely scandalous but also illegal, because Sir Henry was Harriet’s brother-in-law (He had been married to Harriet’s sister, who was now deceased; still, the law prohibited marriage between a man and his late wife’s sister; likewise, a woman could not marry the brother of her deceased husband.)

The charges were uncontested, but a trial was held to determine damages. The jury awarded Lord Rosebery the enormous sum of 15,000 pounds (equivalent to about a million dollars in today’s terms) – the highest amount ever in a crim. con. case.

Lord Rosebery promptly divorced his wife. A year later, Harriet and Sir Henry married, in Germany, “by special permission of the King of Wurttemburg.”

Harriett had three more children with her second husband and they lived happily together for nearly twenty years, until her death in 1834.

[see, http://blogs.princeton.edu/graphicarts/2011/12/criminal_conversation.html ]

The crim. con. cases were reported and publicized by the newspapers. Anyone in Society who hadn’t been aware of the affair before, got to enjoy all the salacious details.

Crim. cons. were the tabloid fodder of the Georgian and Regency eras.

![C [150x150]](https://victoriahodge.files.wordpress.com/2014/04/c-150x1501.jpg?w=474)

I haven’t read this reference in my historical romances yet (or I didn’t notice), but now I’m prepared!

LikeLike